People diagnosed with sleep apnea are often prescribed positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy. PAP therapy pushes air into a sleeper's airway to keep it open and reduce the number of breathing disruptions they have during sleep.

There are multiple devices that can deliver PAP therapy. The type of device prescribed by a doctor depends on several factors, including the type of sleep apnea and a person's medical history. CPAP and APAP devices are the two most common PAP therapies used to treat obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

What Is the Difference Between APAP vs. CPAP?

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines release pressurized air at a nearly steady rate throughout the night. In comparison, auto-adjusting positive airway pressure (APAP or auto-CPAP) machines continually adjust the pressure of air based on what the device determines the sleeper needs in a given moment.

Historically, doctors prescribed CPAP therapy as the primary treatment to people with obstructive sleep apnea, the most common type of sleep apnea. In recent years, APAP therapy has become more common, and is often a first-line treatment for OSA.

CPAP therapy may be prescribed to people with certain types of central sleep apnea (CSA). CSA is a type of sleep apnea in which lapses in breathing occur during sleep because the brain doesn't properly signal the breathing muscles. While other types of PAP therapy may be used to treat CSA, APAP isn't commonly used.

What Is CPAP?

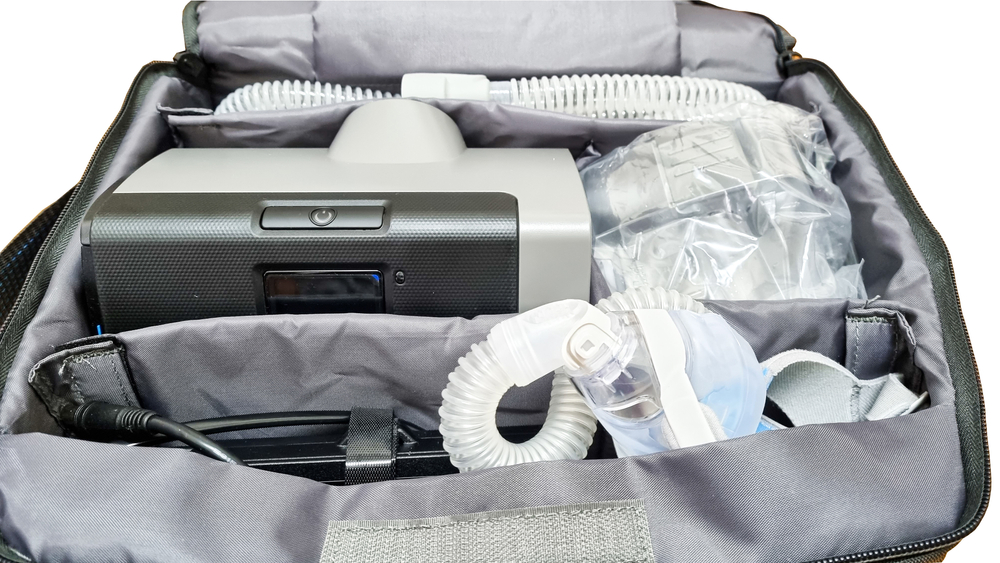

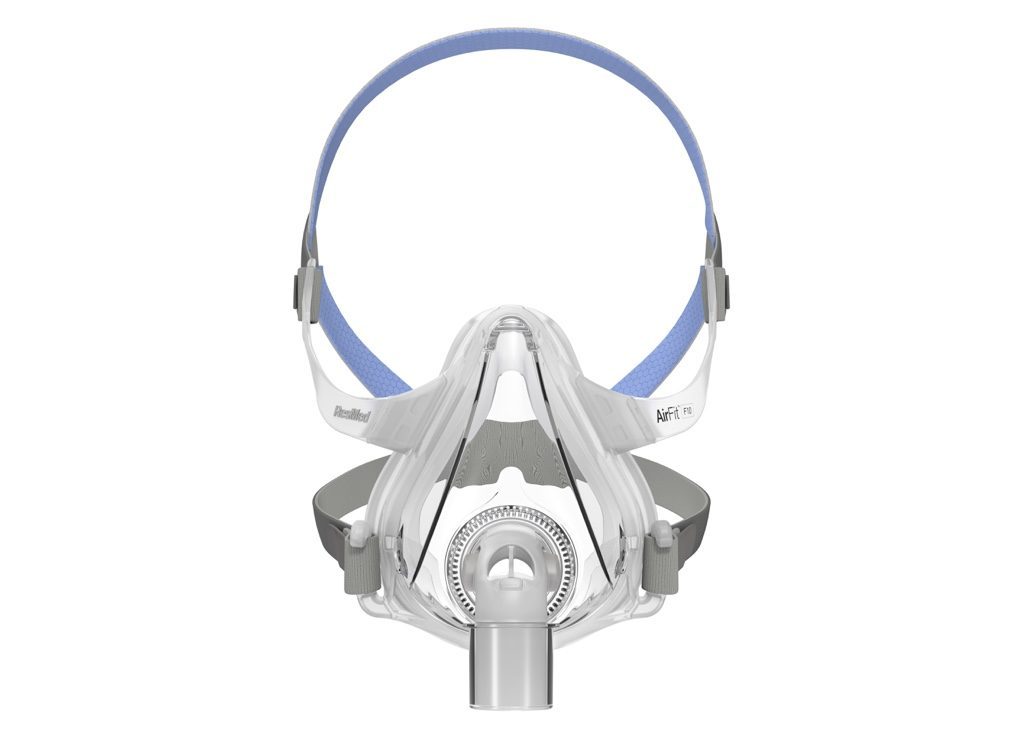

A CPAP machine is a small device that sits next to a person's bed. The machine delivers air through a hose into a mask that seals against a person's face, covering their nose or both their nose and mouth as they sleep. This air helps keep a sleeper's airway open, reducing the number of lapses in breathing that characterize sleep apnea.

Traditional CPAP machines are often called fixed-level CPAPs because the air they release flows at a relatively fixed rate of pressure throughout the night. The optimal level of air pressure is often decided during an overnight sleep study conducted in a lab, but may also be determined by temporarily using an APAP machine at home.

CPAP machines may have features that change air pressure at times to increase comfort. For example, a pressure relief feature reduces pressure when a person begins exhaling to reduce the discomfort of breathing against pressurized air. A pressure ramp feature gradually increases air pressure, so a person can fall asleep before the air reaches the desired pressure.

Another CPAP feature designed to promote comfort is heated humidification. Because PAP therapy can dry out the nasal passages, heated humidification can keep the nose and mouth from becoming too dry. Heated humidification can be particularly useful for people who live in dry or cold regions, and for those who have had certain types of throat surgery.

What Is APAP?

Like CPAP, an APAP is a small machine used to treat sleep apnea. Although it looks and operates similarly to a CPAP, an APAP differs in how it delivers pressurized air. Instead of releasing air at a near-constant rate, an APAP machine frequently alters the pressure of air according to a calculation by the device.

An APAP machine can sense changes in airflow to and from the lungs, such as when a sleeper's breathing has slowed or they have begun snoring. The machine then adjusts its rate of airflow accordingly, using a higher pressure of air to prevent lapses in breathing, then reducing air pressure when a higher rate is unnecessary.

Because an APAP tends to release air at a lower rate of pressure much of the time, some people may find using the machine more comfortable than using a CPAP. Like a CPAP machine, an APAP may also have additional features that add comfort, like pressure relief, pressure ramp, and heated humidification.

Why You Might Use APAP vs. CPAP

While CPAP has traditionally been the gold-standard for treating obstructive sleep apnea, APAP has recently become more commonly prescribed. A sleep specialist may opt to prescribe a person with obstructive sleep apnea an APAP machine for several reasons.

- In-home programming: APAP machines can determine the necessary level of pressure from a person's home, allowing people to avoid an overnight sleep study in a lab. This is especially useful for people who have trouble undergoing a second sleep study or who have insurance that won't cover it.

- Increased comfort: Some people find an APAP machine more comfortable to use than a CPAP machine, because it generally delivers air at a lower average pressure. If a person tries a CPAP machine first and finds it uncomfortable, their provider may have them try an APAP machine instead.

- Variable pressure needs: An APAP machine works best for people who require variable amounts of air pressure because their symptoms vary at different times. For some people, symptoms may worsen when they lie on their back, after drinking alcohol, or when they're experiencing allergies.

- Pregnancy: APAP machines are the preferred PAP therapy for pregnant people. When sleep apnea develops during pregnancy, symptoms may become more severe as pregnancy progresses. Using an APAP can continue to provide adequate treatment as needs change, without the need for another sleep study to determine optimal settings.

However, there are some instances in which sleep specialists may prescribe CPAP rather than APAP therapy.

- Central sleep apnea: People with CSA are often treated with CPAP. There is a lack of research on whether APAP is a beneficial treatment for those with CSA.

- Complicated OSA: Complicated OSA describes when a person has both OSA and another disorder that impacts sleep, like heart failure or COPD. APAP isn't ideal for complicated OSA, so sleep specialists generally prescribed a fixed-level CPAP machine instead.

BiPAP

Bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP or BPAP) is another type of PAP therapy prescribed for sleep apnea. If a person with OSA cannot tolerate using a CPAP or APAP machine, their sleep specialist may have them try BiPAP. BiPAP may also be used in several circumstances for people with CSA.

A BiPAP machine looks and operates similarly to CPAP machines, but releases air somewhat differently. Instead of releasing air at a fixed rate, like CPAP, a BiPAP releases air at two pressures: one as a sleeper breathes in and another as they breathe out. BiPAP devices can also be auto-adjusting, offering a variable rate of pressure depending on a person’s needs.

Potential Side Effects of APAP and CPAP

There are several common side effects of PAP therapy and, in some instances, people with OSA can develop a form of CSA after beginning PAP therapy.

Common PAP Side Effects

PAP therapies can produce side effects, like nasal dryness, congestion, air leaks, or feelings of claustrophobia. Each is addressed individually. For example, heated humidification can often treat dryness, while trying different mask types may reduce air leaks. Practicing wearing a mask for longer and longer periods may ease claustrophobia.

Sometimes people are tempted to not use their PAP machine enough, because they find it to be uncomfortable. For example, they might notice they are waking up more frequently in the night, swallowing air, or experiencing discomfort related to the mask or the feeling of pressurized air. In these instances, a healthcare provider can help remedy the problem and make it easier to use the device consistently.

Treatment-Emergent Central Sleep Apnea

Treatment-emergent central sleep apnea is a type of CSA that develops in 5% and 15% of people who are given PAP therapy for OSA. Certain people are more likely to develop treatment-emergent CSA, including older adults, people assigned male at birth, those with severe OSA, those with heart failure, mouth breathers, and sleepers living at a high altitude.

Over half of people with treatment-emergent CSA have it go away on its own after they continue PAP therapy for a few months. Because treatment-emergent CSA often goes away on its own, it may not require immediate treatment. If treatment-emergent CSA persists, doctors may prescribe a different type of treatment such as BiPAP.

What Are Other Ways to Treat Sleep Apnea?

Beyond PAP therapy, other treatment options for sleep apnea might be recommended depending on the type of sleep apnea and the cause of breathing disruptions.

In addition to PAP therapy, people with obstructive sleep apnea may be advised to make lifestyle changes to reduce their symptoms, including exercise, weight loss, changing sleeping positions, and cutting out alcohol and sedative use. Other treatments for OSA may include surgery, oral appliances, medication, or hypoglossal nerve stimulation.

Central sleep apnea is often treated by addressing underlying medical conditions that are contributing to breathing disruptions. People with CSA may also be treated with supplemental oxygen, medications, or phrenic nerve stimulation.

Still have questions?

Sleep apnea products can be confusing. If you need individualized assistance, post your question to the Sleep Doctor forum.